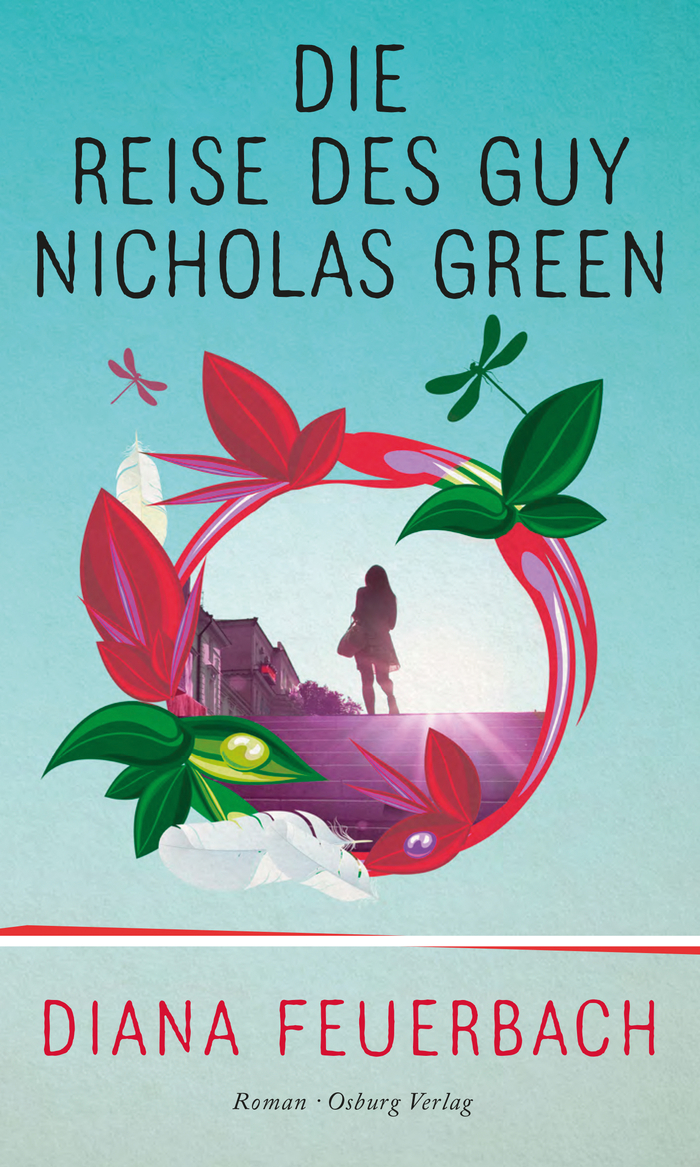

DIE REISE DES GUY NICHOLAS GREEN

»Mein bisheriges Leben tauchte an mir vorüber, als wäre es nicht meins, sondern eine Ansammlung von Erinnerungen, die niemandem gehören.«

zur Verlagswebseite

zur Verlagswebseite

Die Reise des Guy Nicholas Green

Roman, 223 S.

ISBN 978-3-95510-039-1

EUR 14,99

auch als E-Book erhältlich

Inhalt / Content

Der Weltenbummler Guy Nicholas Green strandet in Odessa am Schwarzen Meer. Im Hostel trifft er den jungen Engländer Jamie Durham. Jamie braucht Hilfe: Er will Julia finden, seine ukrainische Traumfrau, die er online kennengelernt hat. Guy hat ganz andere Sorgen, doch er lässt sich hineinziehen in diese fremde Geschichte, die ihn köstlich amüsiert. Heiratstourismus und Online-Dating, Damen auf schwindelerregenden Absätzen, Herren mit Handtaschen, überfüllte Trolleybusse, bunt bevölkerte Nachtclubs … und eine Freundschaft wider Willen.

Globetrotter Guy Nicholas Green gets stranded in the Ukranian town of Odessa. He meets Jamie Durham, a young Englishman. Jamie needs help locating Julia, a Ukrainian girl he has met online. Guy has enough problems of his own, but he welcomes the diversion and gets involved with Jamie’s search. Marriage tourism and online dating, ladies on vertiginously high heels, men sporting male purses, crowded trolley buses and nightclubs ... and an unlikely friendship.

Leseprobe

Kapitel 1: Die Treppe

Meine Erinnerung an Odessa beginnt in einem alten Haus, auf einer Treppe. Ich sehe die Stufen vor mir: das Gebiss eines ausgestorbenen Wesens. Die Lilien im Geländer sind vom Grünspan zerfressen. Von den Wänden schuppen die Reste eines hundertjährigen Anstrichs, und der Fahrstuhlkäfig, elegant geschmiedet und stark verrostet, beschützt eine Kabine, mit der niemand mehr reist. Das Foyer riecht nach Moder, und natürlich ist es dort nie richtig hell geworden. Jedenfalls nicht in den Sommerwochen, die ich Mitte der Nullerjahre in Odessa verbrachte und von denen man sagen kann, dass sie mich wundersam abbrachten von meinem Weg. Die Treppe war für mich damals ein Bild meiner Seele. Auch äußerlich machte ich nicht mehr viel her: fast Mitte vierzig, die blonden Schläfen ergraut, Tränensäcke unter den Augen, ein bitterer Zug um den Mund und ein Adamsapfel, der langsam spitzer wurde unter dem Fleisch.

mehr lesenMehr zum Buch

Besprechung auf MDR Kultur

von Ina Namislo

Interview zum Buch

Moderator: Axel Bulthaupt

The Journey of Guy Nicholas Green - English excerpt

Chapter 1: The Staircase

My memory of Odessa begins on a staircase, in an old building. I see the stairs before me, the teeth of an extinct creature. The lilies in the banister are corroded with verdigris. The remnants of century-old paint are peeling off the walls, and the caged elevator, elegantly wrought and badly rusted, protects a cabin that now carries no one. The foyer smells musty, and of course it’s never well-lit. Or at least it never was during the summer weeks I spent in Odessa back in the mid-aughts, weeks which you might say wondrously threw me off my path. The staircase back then was the image of my soul. Of course on the outside I wasn’t a pretty picture either: nearly in my mid-forties, blond temples graying, heavy bags under my eyes, a bitter line around my mouth, and an Adam’s apple that was slowly growing more pointed under my skin.

You could still tell the stairs were made of marble. I imagined the servant girls of yore, sweeping the white-veined steps with birch brooms. Or sometimes I imagined the steps being covered with Turkish carpets, their birds of paradise singing while people in the elevator chatted with its operator who worked the brass lever and had the most splendid moustache in town. In the revolution and the wars that followed, the stairs trembled under soldiers’ boots, growing weary and finally caving in during the long decades of communism. These stairs were somewhere I felt at peace. Or so I told myself. Slowly climbing the shabby steps to the scraping sound of my sandal soles, I persuaded myself that things were fine, that I’d have to sit tight in this town until Mother would send me more money. I would use the money to travel to India, where I’d promptly dispose of my ego. After that, I would never work again.

Close to the wall where nobody walked, the stairs still had sharp edges and were covered with pigeon droppings. Toward the middle they became more blunt and wavy. There were cracks, crevices, and holes housing mice. Towards the banister the worn-out remnants of steps merged into a yellowish tongue that posed a slipping hazard. Sometimes, in a fit of self-pity, I would take off my sandales in the lobby and walk up in my bare feet, probing with my naked soles the old, teeth-like stairs. Behind me, from the street outside, I could feel the shimmer of sunglasses and the silhouette of the little waitress at the café across the street who served espresso to selfmade businessmen as they made their shady deals. The pedestrian zone where the building was located was called Deribasov Street. This was the main promenade, in the heart of the Old Town as they say in tourist-speak, cobble-stoned and Cyrillic-lettered, lined with lime trees and the awnings of shops and restaurants. Some of the buildings were new and swanky, but most were classicist and art nouveau, weathered and plastered with ads. More than a few façades lay dormant under tarps. The promise of resurrection was in the air, as if the city one day hoped to become what it feigned to have been long ago: a diva on the Black Sea.

It was early July when I washed up on its shores. Actually, I arrived on wheels, in a Moldovan dollar van, a marshrutka. Two days in a jam-packed bus, Eurolines London-Chișinău, had really rattled me. I was hoping to find a cheap boat to Turkey, but most of all that my mother would agree to send me money. The dreary steppe landscape we drove through depressed me. So I closed the curtain of my window, till its threadbare material eventually revealed a distant mass on the dusty horizon. This was the city of Odessa, greeting me in the form of high-rise apartments, just like the ones I’d seen on the outskirts of Romanian and Moldovan cities. I drew the curtain back. I didn’t know the first thing about this city, but I found the name appealing. It sounded like a memory, surely not my own yet somehow familiar.

At the bus station a group of little old ladies offered me accomodations. Dangling their laminated photos in front of me, they tugged at my T-shirt, cajoled me with sibilants and cooing sounds. I was almost twice as tall as they were, these ladies with their gilded incisors - a sign of erstwhile prosperity, perhaps - and whiskers on their chins. The rooms they offered seemed affordable enough, some of them even included meals, but I couldn’t really expect these kind-hearted babushkas to take me in for free, could I. So, shouldering my backpack, I set off down the first avenue. In my hand I held the printout with directions of how to get to the hostel. „Prime location in Odessa’s historical Old Town! Your home away from home in these times of romantic pursuit!“ That’s what it said underneath the map. I’d only skimmed through the description and took the „romantic quest“ for translationese.

Outside the opera house - an imposing Baroque ensemble languishing behind a construction fence - a pack of dogs was dozing. I turned left onto Deribasov Street. The sun was warming the cobblestones, lime tree leaves fluttered gently in the wind, and although it was lunchtime and not too busy I couldn’t help notice the young women. They walked as if they carried their pride in invisible vases on top of their heads. Not swaying their hips like African girls, because strictly speaking they had no hips compared to the sub-Saharan ideal. And yet their high-heeled feet were curved like the horns of gazelles. Briskly they strolled over bumpy stones, cell phones pressed to their ears, shopping bags in arm, and generally showed more skin than the weather seemed to warrant. They gave the impression of being unapproachable as they walked past the rows of cafés and restaurants, eyes protected by shades, and though they must have registered my existence in passing they didn’t even deign to glance at me.

Swallowing my disappointment, I resumed my search for the hostel. The building it was in looked somber. A crack ran through the façade, possibly from an earthquake. I made out a number in the sandstone archway: 1900, each letter riddled with tiny holes. One of the two double doors was propped open and, judging by the way it looked, the year 1900 seemed credible. The hinges were rusted through and the door leaned up against the wall like a forgotten museum display. Inside the entrance I spotted a little sign. Black Sea Hostel. I opened the door of the building, crossed the threshold, and for a moment couldn’t see a thing.

Coolness enveloped me. The smell of urine slowly reached my nostrils. On the wall of the lobby a row of neglected mailboxes disengaged itself from the darkness, a greeting from a bygone era when people still wrote to each other on paper. Straight ahead the stairway emerged. A tourist would have snapped a picture but I held on to the banister. The sight of these stairs made me miserable. The steps, a fruit of more recent decay and Eastern European decadence, were neither moss-covered nor lead to hidden chambers. Yet they clearly gave me a déjà vu. They resembled the secret temple stairs of the Maya, like the ones inside the mysterious pyramids of Guatemala, Honduras and Southern Mexico. My last job, you see, was in Palenque, Mexico - not working as an archeologist in jungle ruins, but as the project manager of an NGO, trying to help the impoverished descendants of the ancient temple-builders. It was there that something happened to me that would cost me my job and eventually send me on this journey. It hadn’t even been a month since, and the wound was still awfully fresh. Never did I expect to reencounter those stairs, more than a hundred meridians to the East, in another part of the world - and this in the very hour of my arrival.

- Translated from the German by David Burnett